Anybody know of any research that has been done pertaining to accidents caused by intercepting false glideslopes? I've been hearing that warning for decades, but the actual risk of this happening seems to be almost vanishingly small. I mean, at twice the angle it's "reversed", which would look weird, and at three times the angle it's "correct" but you'd be literally 3 times the AGL altitude at any given point and therefore require 3x the descent rate (so, like 1500 fpm in a 172), which is bound to get your attention.

If this is actually a problem, I'd be really interested to read some accident reports (or ASRS, ASAP, etc reports).

I'd hypothesize that if this is actually a problem, it was many decades ago, before GPS and DME and RADAR service and other distance-remaining indicators. As in, just flying final with no SA on distance until the glideslope needle starts coming down.

EDIT - We'll I'll be...

Investigators have found that an Air France Airbus A318's stall-protection system activated when the aircraft captured a false glideslope, after its crew lost situational awareness while dealing with a rushed approach to Toulon-Hyeres airport. The aircraft (F-GUGD) had been arriving from Paris...

www.flightglobal.com

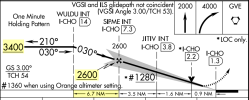

Short version is that the crew was way high, trying to intercept the glideslope from above, and crossed the FAF 500 ft above the published altitude. Therefore, the autopilot did not capture the GS. But they also had the altitude preselect set for 200 ft above the FAF altitude (their last cleared altitude), so after passing the FAF and not capturing the GS, the autopilot leveled off at that altitude and flew level until the 9 deg false glideslope.

The article is confusing, though. It mentions that the 9 deg glideslope is reversed, which is not true, and that the autopilot commands would therefore be backward. The aircraft upon encountering this glidepath pitched up dramatically, which I don't understand either. With a 9 deg glideslope it should have pitched down, just steeper.

If they meant the 6 deg false glideslope, though, when I draw it out in my mind it should still command a descent, as approaching the 6 deg glideslope from below, the needle would be full-scale down, right? And then it would come up to meet you as you fly level towards the false GX intercept.

Spoiler alert, they executed a go-around and returned for a safe landing.