bqmassey

Line Up and Wait

Here is the body of paper I wrote about checklist usage for my human factors class. I'm not a great writer, but here it is anyways.

I'm curious how others were taught to use checklists. I can't recall receiving any instruction specific to it.

Currently I do use challenge-response, even by myself (read left column, touch control, read control status, read right column) but it's something I've started doing fairly recently.

I have the emergency checklists memorized for the aircraft I'm flying, but the startup and shutdown checklists have some complicated and critical parts in them that I still prefer to read from the checklist. Only the parts that have to happen in quick succession are memorized.

-------------------------------------------------

Checklists are an everyday item in the aviation industry. You can find them in the cockpit of anything from the most simple Light Sport Aircraft to a Boeing 787. Any pilot trained in the United States today will be expected to demonstrate the use of a checklist. In fact, it’s currently a Special Emphasis Area in the Federal Aviation Administration’s Practical Test Standards (Private Pilot Practical Test Standards for Airplane). In spite of this, there is often little to no training given in regards to how to use checklists, beyond the simple suggestion that they should be used. From accident investigations, we see that there are ways in which human factors can attenuate the benefit gained from checklists, even in spite of a pilot’s attempt to use the checklist in a thorough and deliberate manner.

HISTORY

In Dayton, Ohio, October 30, 1935, three aircraft manufacturers, vying to be selected for a major U.S. Army Air Corps bomber contract, showed up to demonstrate their submissions. Boeing was present with its formidable Model 299. In the several stages of evaluation leading up to this point, the Model 299 was quite clearly outperforming Martin’s Model 146 and Douglas’s DB-1, so much so that many considered these latter stages to be a mere formality. Boeing executives were excited at the prospect of selling hundreds of airplanes.

Flying the 299 that day were two Army pilots, under the advisement of two representatives from Boeing, and one from engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney. The aircraft made a typical taxi and takeoff. As the Model 299 began to climb, it entered a stall. The lumbering aircraft dropped a wing, followed by a rapid descent into terrain. Of the five aboard, three received serious burns and two were killed.

In the investigation, it was determined that Major Ployer P. Hill, the pilot, had neglected to release the mechanical gust lock on the elevator. One of the Boeing representatives realized what had happened, but couldn’t correct it in time. Many considered the Model 299 project to be dead. It gained the reputation of being too complex, too much for one crew to handle. The contract was awarded to Douglas and production began for 133 DB-1s under the B18 nomenclature.

The Boeing bomber, despite the accident, had some support amongst the flying members of the Air Corps. To appease the pleading of several of its officers, the Army Air Corps agreed to purchase thirteen Boeing Model 299 for further testing. Twelve of these were delivered to pilots of the 2nd Bombardment Group in Langley, Virginia with the direction that any further accidents would be the end of the 299’s service.

The pilots of the 2nd decided they needed a way to prevent accidents like that in Dayton. They devised four checklists: takeoff, flight, before landing, and after landing. With the advent of checklists and proper training, the twelve Model 299s flew 1.8 million miles without a serious accident. The U.S. Army began placing orders for the Model 299, eventually purchasing 12,731 of these aircraft, which were put into service as the B-17 “Flying Fortress” (Schamel).

Checklist usage quickly caught on, becoming standard practice for the U.S. Army Air Corps (now the United States Air Force) and later adopted on a wide scale by both military and civilian aviation.

“CHECK” LIST OR “DO” LIST?

It’s not a rare sight, a student pilot with a checklist in one hand, moving methodically down the list, setting levers and switches line by line, like an inexperienced cook executing a complex recipe. It is, without a doubt, a thorough way to proceed, but is it efficient? Is it prone to error? Is the pilot even capable of getting airborne without the checklist reminding him how to proceed?

The converse of this is the pilot that uses no checklist. Tasks are completed as they come to mind. The order of procedures might not be consistent between flights. Cautionary items that are only occasionally necessary might be forgotten with time.

Which of these two methods is the better practice? Should you be heavily dependant on your checklist, or does it become obsolete once you’re familiar with your aircraft? Many would say somewhere in between. Some would say that pilots should do both.

A common tactic in Crew Resource Management (CRM) is to use the checklist truly as a “check” list, instead of a “do” list. In other words, the checklist is used as a means of verification, not a set of instructions. When a configuration change is necessary, one pilot will make all of the changes based on memory. Once completed, the checklist is referenced, as time permits, to ensure completeness and accuracy. This is a dramatically different technique than the “say-do” method, where one pilot reads verbatim from the checklist as the second pilot executes the commands (the “cookbook method” in a single-pilot environment).

Checklist use being limited to verification allows the aircraft to be reconfigured quickly, as can be accomplished by pilots who don't use checklists. The error rate inherent to this style of flying is then mitigated by using the checklist to verify settings. Using the checklist in this way allows for a reliance on checklist memorization, without being as vulnerable to lapses in memory or judgement.

Using the checklist for verification doesn’t relieve the pilot of the responsibility to be complete and accurate when relying on memory. To assist in this, many pilots, aircraft manufacturers, and operators organize checklist items into “flow patterns”. This aids in memorization by placing items in an order based on physical location within the cockpit. For example, if faced with an engine failure in a Cessna 172, a pilot could use an “inverted L” flow pattern. He starts with the fuel selector on the floor, moves up to set the mixture, then crosses left to set throttle, set the carburetor heat, check the magnetos, and set the primer. Flow patterns such as this are common in the airlines, and are published in the air carriers training manuals (Rossier).

The process of using a flow pattern to change aircraft configurations, and then verifying with a checklist as time permits, is one that could—perhaps should—be used in any cockpit. Except in certain circumstances, such as when a checklist hasn’t yet been memorized or when it’s critical that certain steps be conducted in a particular and non-obvious order, using a checklist as “check” list instead of a “do” list has many advantages.

CHALLENGE-RESPONSE

Checklist usage isn’t immune to human factors. Expectation bias can, and has, resulted in fatal mistakes in the application of checklists. Accidents have resulted from a pilot reading a checklist item, looking at the control or switch that is in the wrong position, perceiving that it is as the checklist describes, and continuing with the checklist.

Where a flow pattern with checklist verification provides a protection against incomplete checklists, the “challenge-response” technique helps prevent inaccurately executed checklists.

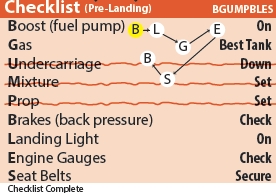

The challenge-response technique considers the checklist item, typically the left column, to be the “challenge”. The setting, typically in the right column, is the “response”. In a crew environment, the pilot with the checklist announces the challenge. The second pilot touches the switch/control, placing it in the necessary position if it isn’t already there, and then reads the position that it is in. It’s critical that this pilot does not immediately reply with the necessary switch position, but rather responds with the setting as he reads it. The pilot with the checklist, after reading the challenge, waits for the response and verifies against what is on the checklist.

The challenge-response technique has an added benefit of making sure that the pilots share an understanding of the aircraft’s configuration. For example, many airplanes’ approach checklists will list “FLAPS...... SET”. In this case the checklist pilot reads “FLAPS”, the second pilot sets that flaps to what is appropriate for that approach, and responds with “20 degrees”. By responding with what he is reading (“20 degrees”), and not what the checklist response is (“SET”), the checklist pilot knows that the flaps are deployed and also to what setting they are deployed.

Challenge-response is not only a CRM tactic. It is employable and beneficial to the single-pilot cockpit as well. In a similar fashion, the pilot reads the challenge, touches the control and moves it if necessary, reads the present setting, and then compares it to the checklist.

THE TAKE-AWAY

There are three steps that a pilot can take that might significantly enhance the effectiveness of their checklists:

1. Commit checklists to memory, using flow patterns for speed and completeness.

2. Use checklists for verification as time permits, not for step-by-step instructions.

3. Use challenge-response, even in single-pilot operations, to ensure accuracy.

Since their advent in the 1930’s, checklists have had a significant impact on aviation safety. Despite this impact, there is still more that can be done to enhance the benefit we receive from what seems like such a simple tool. Through training and human factors research, the industry will continue to evolve the accepted best practices. These changes often miss the private aviators and small operators. It’s in the best interest of any current pilot to evolve his knowledge and techniques as we learn more about how to aviate skillfully and safely.

I'm curious how others were taught to use checklists. I can't recall receiving any instruction specific to it.

Currently I do use challenge-response, even by myself (read left column, touch control, read control status, read right column) but it's something I've started doing fairly recently.

I have the emergency checklists memorized for the aircraft I'm flying, but the startup and shutdown checklists have some complicated and critical parts in them that I still prefer to read from the checklist. Only the parts that have to happen in quick succession are memorized.

Checklists are an everyday item in the aviation industry. You can find them in the cockpit of anything from the most simple Light Sport Aircraft to a Boeing 787. Any pilot trained in the United States today will be expected to demonstrate the use of a checklist. In fact, it’s currently a Special Emphasis Area in the Federal Aviation Administration’s Practical Test Standards (Private Pilot Practical Test Standards for Airplane). In spite of this, there is often little to no training given in regards to how to use checklists, beyond the simple suggestion that they should be used. From accident investigations, we see that there are ways in which human factors can attenuate the benefit gained from checklists, even in spite of a pilot’s attempt to use the checklist in a thorough and deliberate manner.

HISTORY

In Dayton, Ohio, October 30, 1935, three aircraft manufacturers, vying to be selected for a major U.S. Army Air Corps bomber contract, showed up to demonstrate their submissions. Boeing was present with its formidable Model 299. In the several stages of evaluation leading up to this point, the Model 299 was quite clearly outperforming Martin’s Model 146 and Douglas’s DB-1, so much so that many considered these latter stages to be a mere formality. Boeing executives were excited at the prospect of selling hundreds of airplanes.

Flying the 299 that day were two Army pilots, under the advisement of two representatives from Boeing, and one from engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney. The aircraft made a typical taxi and takeoff. As the Model 299 began to climb, it entered a stall. The lumbering aircraft dropped a wing, followed by a rapid descent into terrain. Of the five aboard, three received serious burns and two were killed.

In the investigation, it was determined that Major Ployer P. Hill, the pilot, had neglected to release the mechanical gust lock on the elevator. One of the Boeing representatives realized what had happened, but couldn’t correct it in time. Many considered the Model 299 project to be dead. It gained the reputation of being too complex, too much for one crew to handle. The contract was awarded to Douglas and production began for 133 DB-1s under the B18 nomenclature.

The Boeing bomber, despite the accident, had some support amongst the flying members of the Air Corps. To appease the pleading of several of its officers, the Army Air Corps agreed to purchase thirteen Boeing Model 299 for further testing. Twelve of these were delivered to pilots of the 2nd Bombardment Group in Langley, Virginia with the direction that any further accidents would be the end of the 299’s service.

The pilots of the 2nd decided they needed a way to prevent accidents like that in Dayton. They devised four checklists: takeoff, flight, before landing, and after landing. With the advent of checklists and proper training, the twelve Model 299s flew 1.8 million miles without a serious accident. The U.S. Army began placing orders for the Model 299, eventually purchasing 12,731 of these aircraft, which were put into service as the B-17 “Flying Fortress” (Schamel).

Checklist usage quickly caught on, becoming standard practice for the U.S. Army Air Corps (now the United States Air Force) and later adopted on a wide scale by both military and civilian aviation.

“CHECK” LIST OR “DO” LIST?

It’s not a rare sight, a student pilot with a checklist in one hand, moving methodically down the list, setting levers and switches line by line, like an inexperienced cook executing a complex recipe. It is, without a doubt, a thorough way to proceed, but is it efficient? Is it prone to error? Is the pilot even capable of getting airborne without the checklist reminding him how to proceed?

The converse of this is the pilot that uses no checklist. Tasks are completed as they come to mind. The order of procedures might not be consistent between flights. Cautionary items that are only occasionally necessary might be forgotten with time.

Which of these two methods is the better practice? Should you be heavily dependant on your checklist, or does it become obsolete once you’re familiar with your aircraft? Many would say somewhere in between. Some would say that pilots should do both.

A common tactic in Crew Resource Management (CRM) is to use the checklist truly as a “check” list, instead of a “do” list. In other words, the checklist is used as a means of verification, not a set of instructions. When a configuration change is necessary, one pilot will make all of the changes based on memory. Once completed, the checklist is referenced, as time permits, to ensure completeness and accuracy. This is a dramatically different technique than the “say-do” method, where one pilot reads verbatim from the checklist as the second pilot executes the commands (the “cookbook method” in a single-pilot environment).

Checklist use being limited to verification allows the aircraft to be reconfigured quickly, as can be accomplished by pilots who don't use checklists. The error rate inherent to this style of flying is then mitigated by using the checklist to verify settings. Using the checklist in this way allows for a reliance on checklist memorization, without being as vulnerable to lapses in memory or judgement.

Using the checklist for verification doesn’t relieve the pilot of the responsibility to be complete and accurate when relying on memory. To assist in this, many pilots, aircraft manufacturers, and operators organize checklist items into “flow patterns”. This aids in memorization by placing items in an order based on physical location within the cockpit. For example, if faced with an engine failure in a Cessna 172, a pilot could use an “inverted L” flow pattern. He starts with the fuel selector on the floor, moves up to set the mixture, then crosses left to set throttle, set the carburetor heat, check the magnetos, and set the primer. Flow patterns such as this are common in the airlines, and are published in the air carriers training manuals (Rossier).

The process of using a flow pattern to change aircraft configurations, and then verifying with a checklist as time permits, is one that could—perhaps should—be used in any cockpit. Except in certain circumstances, such as when a checklist hasn’t yet been memorized or when it’s critical that certain steps be conducted in a particular and non-obvious order, using a checklist as “check” list instead of a “do” list has many advantages.

CHALLENGE-RESPONSE

Checklist usage isn’t immune to human factors. Expectation bias can, and has, resulted in fatal mistakes in the application of checklists. Accidents have resulted from a pilot reading a checklist item, looking at the control or switch that is in the wrong position, perceiving that it is as the checklist describes, and continuing with the checklist.

Where a flow pattern with checklist verification provides a protection against incomplete checklists, the “challenge-response” technique helps prevent inaccurately executed checklists.

The challenge-response technique considers the checklist item, typically the left column, to be the “challenge”. The setting, typically in the right column, is the “response”. In a crew environment, the pilot with the checklist announces the challenge. The second pilot touches the switch/control, placing it in the necessary position if it isn’t already there, and then reads the position that it is in. It’s critical that this pilot does not immediately reply with the necessary switch position, but rather responds with the setting as he reads it. The pilot with the checklist, after reading the challenge, waits for the response and verifies against what is on the checklist.

The challenge-response technique has an added benefit of making sure that the pilots share an understanding of the aircraft’s configuration. For example, many airplanes’ approach checklists will list “FLAPS...... SET”. In this case the checklist pilot reads “FLAPS”, the second pilot sets that flaps to what is appropriate for that approach, and responds with “20 degrees”. By responding with what he is reading (“20 degrees”), and not what the checklist response is (“SET”), the checklist pilot knows that the flaps are deployed and also to what setting they are deployed.

Challenge-response is not only a CRM tactic. It is employable and beneficial to the single-pilot cockpit as well. In a similar fashion, the pilot reads the challenge, touches the control and moves it if necessary, reads the present setting, and then compares it to the checklist.

THE TAKE-AWAY

There are three steps that a pilot can take that might significantly enhance the effectiveness of their checklists:

1. Commit checklists to memory, using flow patterns for speed and completeness.

2. Use checklists for verification as time permits, not for step-by-step instructions.

3. Use challenge-response, even in single-pilot operations, to ensure accuracy.

Since their advent in the 1930’s, checklists have had a significant impact on aviation safety. Despite this impact, there is still more that can be done to enhance the benefit we receive from what seems like such a simple tool. Through training and human factors research, the industry will continue to evolve the accepted best practices. These changes often miss the private aviators and small operators. It’s in the best interest of any current pilot to evolve his knowledge and techniques as we learn more about how to aviate skillfully and safely.