Clip4

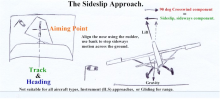

Final Approach

You pointed out the problem of Cirrus exiting the runway. You have to be on the runway to exit it. Aileron will not stop the airplane from yawing into the wind and exiting the runway after touch down. Rudder is required for that. Airplane that exit the runway due to wind exit to the upwind side.I’m proficient, and I’m telling you, if you land or take off in a Cirrus with no crosswind correction on a stiff crosswind day (let’s say above 10 knots), the nose will turn into the wind in the roll. Proper technique will take care of it. Above 15 the wing can lift if you leave the ailerons neutral. The interconnect has nothing to do with it. I’m flying g6 now, but it was the same with the trainers I used to fly.

Last edited: