jasc15

Pre-takeoff checklist

I do not have an instrument rating, nor do I have an HP/complex endorsement, but in reading Eckalbar's IFR - A Structured Approach, and Flying High Performance Singles and Twins I like his numbers approach.

Currently I 'saw' the throttle into position when I am descending and getting into the pattern, which adds to the workload at this part of any flight. Now, this experiment is rather trivial in a trainer with only pitch, power, and flaps to control, but I think this will help me out greatly.

My plan is simply to do some pattern work and write down the pitch, power and flap settings that give me what I need for that phase of the flight, and remember them. Easy enough; it's a machine and only does what you tell it.

Anyone done this test flight? I'd like to make this worthwhile so I want to consider things I may not yet have thought about.

A “by-the-numbers” pilot does not saw back and forth with the throttle trying to find out how much power it takes to stop his or her descent at the MDA. The “numbers” pilot does an experiment one time, finds what works, and from that point on simply dials up the appropriate PAC [power, attitude, configuration] when the need arises.

Currently I 'saw' the throttle into position when I am descending and getting into the pattern, which adds to the workload at this part of any flight. Now, this experiment is rather trivial in a trainer with only pitch, power, and flaps to control, but I think this will help me out greatly.

My plan is simply to do some pattern work and write down the pitch, power and flap settings that give me what I need for that phase of the flight, and remember them. Easy enough; it's a machine and only does what you tell it.

Anyone done this test flight? I'd like to make this worthwhile so I want to consider things I may not yet have thought about.

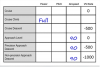

when the emphasis should be on perfecting "the numbers" for the six configurations: climb, cruise, cruise descent, approach, approach descent, and non-precision descent.

when the emphasis should be on perfecting "the numbers" for the six configurations: climb, cruise, cruise descent, approach, approach descent, and non-precision descent.