tonycondon

Gastons CRO (Chief Dinner Reservation Officer)

like this

Thank you! I was trying to find a good picture to demonstrate that the front wheels and nose cone assembly often break away. That's an extreme example mind you, but it makes the point that EppyGA was trying to get across.like this

Exactly what I was thinking. I mean the company has already demonstrated a blatant disregard for the safety issues and continued to market the aircraft to persons who have no business flying it. Should we expect anything but more of that from the rank and file sales person?

As far as the marketing standards, etc....I agree it's a double standard but once again, let's stay focused on the issue at hand.

So far as I am aware they have to pass crash tests to be declared roadworthy. I don't really understand the automotive side of things all that well beyond the basics since it's not my area of interest.

Of course IndyCar drivers wear NOMEX suits, boots, gloves, helmets, and flameproof balaclavas.

I doubt many passengers would enjoy suiting up that way.

Ok I understand that. TNX!!So it was badly worded. Point I was making is that generally the injuries are to the feet and legs in accidents where the impact is close to head on to the wall as the front structure disintegrates.

Geesh Dan, if passengers were going to wear all of that, why not add bubble wrap <g>. Several layers would absorb the shock and if they got ejected from the cockpit, they could go pop, pop, pop all they way down the runway

Best,

Dave

An airplane isn't a car ... and well... pulling the chute too low could be pretty disastrous.

That's the problem: the residual structure is what protects the occupants. Granted a lot of metal aircraft out there don't do an ideal job of it, but composites fail upon impact rather than deforming which gives ZERO occupant protection

which may explain why you seldom see survivors in crashes of composite aircraft where as it is far more common to see non-fatal crashes (even if you exclude "non-crashes" like runway overruns, hard landings, etc) in aircraft built of more traditional materials.

We technically don't know that so let's not make assumptions based on facts not in evidence, OK?

Exactly what I was thinking. I mean the company has already demonstrated a blatant disregard for the safety issues

and continued to market the aircraft to persons who have no business flying it.

I have not read this entire thread, this may have already been brought up. I started a thread a few months ago about joy stick vs. yoke or stick flight controls. I am wondering if, under extreme stress situations, such as this fellow was in, if he could have been applying somewhat more aileron and elevator control than was needed?

A stick or yoke requires a whole lot more movement than a joy stick does for pitch and bank maneuvers, I would think. I've never used a joy stick, so I'm asking what y'all think?

Deformation of metal and shattering of composites both require energy to happen, thus either one is absorbing energy. Just because the composite ends up in a zillion little pieces doesn't mean it didn't provide any protection during the breaking process.

A) You can train in a 172, take your checkride after having mastered the easy bird, buy a Cirrus, get 5 hours of dual in the Cirrus to obtain your HP endorsement and make the insurance company happy, and off you go.

I'd be willing to bet money that most of the Cirrus accident pilots chose option "A" and would have done better had they learned to fly in the Cirrus.

It's hard to speculate without much reliable data but I'd be surprised if the Cirrus "roll cage" would disintegrate in what would be a survivable crash if that cage were made of steel tubing of equal strength. I've seen several fiberglass boats that "disintegrated" in a high energy collision and generally it was the "skin" that turned to dust while the stringers and other structural components remained relatively intact. I'd bet that the same is true of fiberglass wing spars.True, but I was pointing out that once it shatters, whatever is behind it (such as a pilot) is going to be more or less exposed to the ground, trees, etc which is not the case nearly as often in non-composite aircraft. It like comparing a bumper and a windshield: both will absorb force, but once the windshield shatters it's not going to do a whole hell of a lot for the rest of the crash sequence except potentially become flying debris.

It seems to me that virtually every manufacturer of "high performance" airplanes markets them to the "affluent and often cock sure" crowd. They'd be fools not to since those folks are the only ones with the cash to spend on a $500k-$1MM airplane for personal use. Cirrus has just managed to be better at this but at the same time they've gone much further than any other manufacturer regarding training programs and other preventative safety measures IMO.your stance that there is nothing wrong with marketing the Cirrus line to the affluent and often cock sure section of our society is no more valid than my assessment (and that of many others, although you know what they say about what everyone agreeing can mean) that it's a bad idea to encourage a low hour pilot to fly an unforgiving high performance aircraft.

Not to start a debate but I have an interesting academic question to pose: Suppose you find credible evidence that starting people out in Cirrus SR22s from the get-go actually makes them safer in operating them. Would that not raise the question of where do you cut off the "Oh, I'm going to fly higher performance singles" exception to training. I mean if I were to go out and buy a Pilatus or a Mooney or a V-tail Bonanza because that's what I want to fly would you think it's a good idea for me to start out in one of those? What if I hit the lottery and decided to buy a P-51?

Bull****. I've said it before and I'll say it again. There is ABSOLUTELY NOTHING WRONG with marketing the Cirri to anyone, and there is nothing wrong with learning to fly in a Cirrus, even an SR22, especially if that's what you're going to be flying.

You know what I'd really like to see? An analysis of how the Cirrus accident pilots were trained. There's two ways to get out on your own in an SR22: A) You can train in a 172, take your checkride after having mastered the easy bird, buy a Cirrus, get 5 hours of dual in the Cirrus to obtain your HP endorsement and make the insurance company happy, and off you go.

Or, B) you can buy the SR22 right out of the gate, and you'll have to spend a lot more time training to be able to pass the PTS in this faster bird, but when you have your ticket you'll know the Cirrus REALLY well.

I'd be willing to bet money that most of the Cirrus accident pilots chose option "A" and would have done better had they learned to fly in the Cirrus.

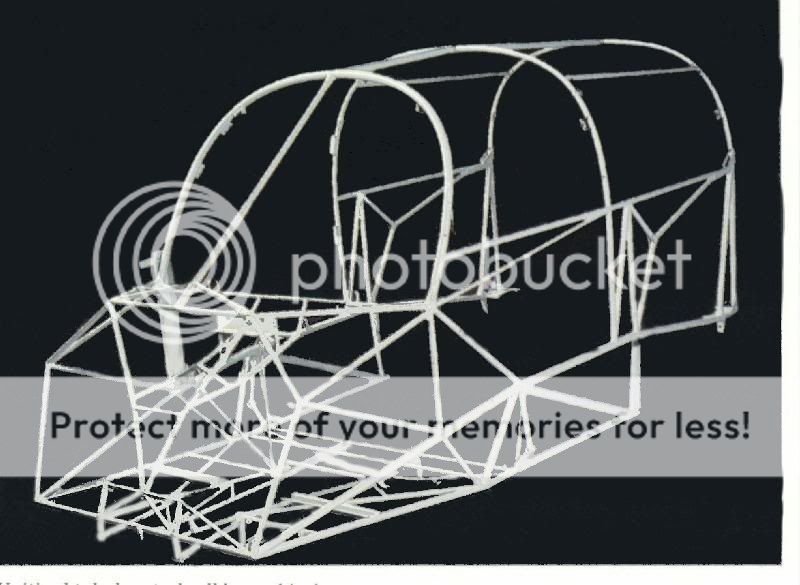

None visible in this photo of the first production Cirrus crash:Interestingly, I got a call from a Cirrus salesman this morning (one of the benefits of sitting in Cirri and leaving your name with the salesmen at AirVenture.) I asked about this accident, which he knew about, and which he saw the pictures of. I asked about crashworthyness of the composites, and he mentioned that Cirrus has a roll cage around the cabin....

However, this Cirrus Web Page says it's got a "3-G Roll Cage."

Perhaps it was added later....

Ron Wanttaja

I'd question how effective a roll cage is when it's anchored to a composite structure that's going to fracture/disintegrate.

Trapper John

I'd question how effective a roll cage is when it's anchored to a composite structure that's going to fracture/disintegrate.

Trapper John

I'm not so sure the Cirrus from the word "go" idea is a good one but if you can provide evidence that it reduces the crash rate after training and that the crash rate during training is lower, you'll have my support on that one.

Until you or someone else with the inclination puts forth the credible evidence you seek, your stance that there is nothing wrong with marketing the Cirrus line to the affluent and often cock sure section of our society is no more valid than my assessment (and that of many others, although you know what they say about what everyone agreeing can mean) that it's a bad idea to encourage a low hour pilot to fly an unforgiving high performance aircraft.

It really is a good airplane - The most "unforgiving" thing about it is that it goes fast (which can be remedied by pulling the throttle back when the plane starts to catch up to you) and it lands fairly fast. It is not difficult to fly by any stretch of the imagination.

It really is a good airplane - The most "unforgiving" thing about it is that it goes fast (which can be remedied by pulling the throttle back when the plane starts to catch up to you) and it lands fairly fast. It is not difficult to fly by any stretch of the imagination.

....or the training fatality rate could spike which seems to be more of the case based on the available evidence.

If you can prove my suppositions incorrect, more power to you and I'll buy you a beer (or burger or whatever) either way to celebrate the day we have the data to use in determining which one of us is closer to correct.

Not to start a debate but I have an interesting academic question to pose: Suppose you find credible evidence that starting people out in Cirrus SR22s from the get-go actually makes them safer in operating them. Would that not raise the question of where do you cut off the "Oh, I'm going to fly higher performance singles" exception to training. I mean if I were to go out and buy a Pilatus or a Mooney or a V-tail Bonanza because that's what I want to fly would you think it's a good idea for me to start out in one of those? What if I hit the lottery and decided to buy a P-51?

None visible in this photo of the first production Cirrus crash:

However, this Cirrus Web Page says it's got a "3-G Roll Cage."

Perhaps it was added later....

Ron Wanttaja

Kent: The fellas that flew P-51s in WWII started in the T-6 IIRC and were in the 51s in a pretty short period of time.

We might ask if anyone knows one of these folks and can ask. I'm pretty sure that's what more than one fella that flew those told me. Many flew the 51 solo first flight as there weren't a lot of two place birds around (P-51s that is).

I know things have changed a lot, but is boosts the argument it can be done. I'm sure there were higher accident rates. What seems to have changed is our acceptance of accidents. Of course, in time of war it changes, but rates are pretty low today compared to some past periods. The Cirri get a lot of attention because they are expensive GA aircraft, the pilots are usually well known, and the crashes often occur in someone's neighborhood.

Best,

Dave

Kent: The fellas that flew P-51s in WWII started in the T-6 IIRC and were in the 51s in a pretty short period of time.

He said that something like 45 new B-17 crews were making the trip across the pond at the time, and that over 2/3 of them never made it.

He said that something like 45 new B-17 crews were making the trip across the pond at the time, and that over 2/3 of them never made it. Another reason we have accidents? Could attitude play a role?

Jumping without a chute: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VZnjgA2K6Dw

Best,

Dave

Yep - But nobody started in the -51.

A few months ago I attended a presentation by a WWII B-17 pilot. They had a whopping 65 hours of flight time, first in a single-engine trainer, then a twin-engine trainer (that had very poor flight characteristics), and a quickie checkout in the B-17, before they were handed a brand-new B-17 to ferry across the pond.

When they were out over the ocean, flying along at 10,000 feet, they started picking up ice. Having never been taught anything about airframe icing or what to do, they kept motoring along, until they could no longer maintain altitude. They went all the way down until they were basically in ground effect before they could maintain altitude, and the salt spray off the ocean melted the ice off the plane.He said that something like 45 new B-17 crews were making the trip across the pond at the time, and that over 2/3 of them never made it.

Unfortunately, the NTSB does not provide us with enough info to make that determination one way or the other.

Isn't it lying on the ground next to the plane?

and that over 2/3 of them never made it

Have you ever flown a Cirrus? I wouldn't call it unforgiving.

No big deal according to him, they were all pretty much the same.

Uncle Jim said the Mustang was much easier to fly than the T-6. The standing joke was that it should have been the trainer.

Just as a data point, the first time my dad manipulated the controls of an aircraft in flight was in an A-26 flying over occupied Germany after the war. Dunno if he ever did a landing or takeoff... (he was a crew chief)

That appears to be the windscreen with possibly the front part of the "roll cage" attached to its rear aspect. Regardless, the idea of having a "half cage" attached to frangible material as occupant protection and painting it to be the equivalent of a metal full protective cage is laughable.

When I asked a Cirrus rep, he said it is "rated to 3 g" as in the acceleration due to the force of gravity (the common usage of g, at least outside of the ghetto). He didn't seem to know much more about it and he really didn't like that I pointed out (in front of a bunch of potential customers) of a group that 3 g is a very low force. As one of my biomedical engineering professors pointed out, if you slam hard on your brakes at highway speed you'll experience around that that during a maximal deceleration stop.It just says it's a 3g cage

When I asked a Cirrus rep, he said it is "rated to 3 g" as in the acceleration due to the force of gravity (the common usage of g, at least outside of the ghetto). He didn't seem to know much more about it and he really didn't like that I pointed out (in front of a bunch of potential customers) of a group that 3 g is a very low force. As one of my biomedical engineering professors pointed out, if you slam hard on your brakes at highway speed you'll experience around that that during a maximal deceleration stop.

Three g is not a terribly high impact force. Hell, prior to the experiments by Stapp and his colleagues, the assumption was that the human body could not routinely survive a deceleration of greater than 18 g. This mistaken belief had a lot to do with how the restraints used in the early years fared and how the integrity of the surrounding cockpit/passenger compartment was maintained (or rather, was not). There is a reason why the FAA started mandating 16 g rated seats in airliners which is an improvement of the 1950s standard 9 g seat that predated them.

I would like to point out that it's not uncommon at all to see survivable car crashes running somewhere around 20-25 g, especially with a young occupant who is properly restrained. If you get really hardcore about impact dynamics, take a look at some of the NASCAR data where impacts of 50-100 g happen with regularity and the roll cage holds up. Not ideally applicable for aircraft due to weight restrictions, but it makes the idea of a 3 g case as "protection" seem laughable. The research of Dr. Stapp and his team showed that aircrew can routinely survive decelerations of 32 g (that's about 315 m/s squared, for those of you who are paying attention to the physics involved) if the seat remains attached and the restraints do not fail. One or both of these contingencies fail to occur in a lot of crashes (both of Cirri and other aircraft as well). This is one of the reasons why having such a low standard for failure of a protective mechanism is, not to point to fine of a point on it, just plain stupid especially if you're going to use it to tout the safety of your aircraft in a crash.

Is there any chance that the roll cage is there to prevent death in case of accidental flip over accidents? For example, landing on grass and snagging the nosewheel in a gopher hole?

In that case, 3 Gs is probably plenty.

I would say there are "crash" scenarios that result in the airplane ending up on its back.That's what I originally suspected (and agree that it would be potentially useful for that purpose) but according to two different reps I've talked to, they are playing it as a safety feature in "crashes" not noseovers.

Most of those are going to involve an impact to the roof of >3 g. About the only one I can think of that would not exceed that would be a slow (relatively speaking) noseover from putting the nose of the aircraft down an incline or into a ditch.I would say there are "crash" scenarios that result in the airplane ending up on its back.