CMTowner

Line Up and Wait

I would make the crossing without hesitation.

Lake St. Clair isn't as cold in July-August as the middle of Lake Michigan. And there is a lot more boat traffic out there in summer than in the middle of Lake Michigan (or Huron or Superior for that matter).At least you don't assume some stranger is obliged to hunt for you and save your butt. IMO, you can assume you're going to die if you can't make it back to the shoreline, winter or summer, in any of the Great Lakes including Lake St Clair.

I would say that you should be instrument proficient, which is not necessarily the same thing as being IFR proficient. The latter implies the former, but not vice-versa. It is possible to be instrument proficient without even being instrument rated.2. One thing I haven't seen mentioned is the possible loss of horizon references depending on altitude and visibility. Many accidents have occured over large lakes where the pilot simply became disoriented due to the water reflecting the sky and losing the horizon. I would not attempt based on this unless IFR proficient.

Most of you guys are full of BS--bravado supremo. I grew up on the south shore of Lake Erie and spent much of my flying career over one or another of the Lakes, always in at least a twin and mostly in twin-engine jets. Do it in a single-engine corn popper? No way, Jose. See the current thread about the cracked cylinder over Coney Island.

dtuuri

On the plus side, if you wind up in the water you could get to see some fantastic images before you go down for the count.

dtuuri

If anyone wants to see what they are flying over or if just curious, there are many maps out there showing current surface temps

Great Lakes, a bit nippy

My crossing

Golfo de México

Warm? As I recall my mother used to call us out of the water when our lips turned blue and our teeth were chattering. As for freighters, for the past two years I've lived almost exclusively six houses back from the shore. I can see the lake from my front yard. Hardly ever see a freighter anymore. Just mentioned it to a friend two days ago, "Where'd they all go?"I know for a fact that Lake Erie is warm enough for swimming in the summer, and it also has quite a bit of large ship (lake freighter) traffic.

Pond, huh? It's 55 miles across where I live, a whole lot farther lengthwise. How do you plan to survive? Bring a life raft? Ever seen one? Do you keep current certified life vests in your plane? The lake has a funny way of getting bigger and bigger as you descend out of altitude--it seems like you're getting farther from land than nearer.That gives you a really strong shot at surviving a ditching in that pond during the warmer months. As a bonus, there is no aquatic wildlife to eat you in that lake.

...

5) I realize that even crossing a body of water like the great lakes usually only leaves you exposed to an open water landing for a few minutes of the flight… if you are high enough you are only really out of gliding range for 10-15 minutes(?)

...

Warm? As I recall my mother used to call us out of the water when our lips turned blue and our teeth were chattering. As for freighters, for the past two years I've lived almost exclusively six houses back from the shore. I can see the lake from my front yard. Hardly ever see a freighter anymore. Just mentioned it to a friend two days ago, "Where'd they all go?"

Pond, huh? It's 55 miles across where I live, a whole lot farther lengthwise. How do you plan to survive? Bring a life raft? Ever seen one? Do you keep current certified life vests in your plane? The lake has a funny way of getting bigger and bigger as you descend out of altitude--it seems like you're getting farther from land than nearer.

dtuuri

Ummm no! At least not in the aircraft that I've done it in.

I flew over Lake Michigan once, and once only, in my 20's, while in a C150. I flew to 10,500 feet, and started westbound over Holland, Michigan, heading towards Milwaukee, Wisconsin. I assumed, without doing the math, that at 10,500 feet I would be within gliding distance of shore for most of my flight. After 10 minutes heading west, I started to lose slight of land in all directions, and THEN I did the math: at 10,500 feet, the vast majority of your trip is not within gliding distance (over 50 NM of it, actually), when the lake is 80 NM across.

I flew for waaaaaaay longer than I was comfortable before seeing land, and I've never done that again.

I would manage the risk by not flying beyond power off gliding distance of shore in a single. Those who do so without survival equipment aren't "managing risk", they're "trusting to luck". Even still, life rafts are cumbersome, might not make it out of the plane before it sinks and life vests are supposed to be inspected and certified and what might be suitable for a river or stream isn't good for off-shore use. Rental planes may not have them available due to lack of demand. It takes an effort to be equipped properly.There is risk in flying, period. Managing these risks is part of the discussion.

As a whole, posts that say "I do it all the time" give the reader what's called "survivorship bias." You don't read counterpoint posts by those who died doing it, because they can't post. Just the posts of those who have survived so far.

Reminds me of riding motorcycles without helmets. You see a lot of people posting on bike forums: "I've been doing it for years and look, I am still here, it hasn't killed me." The reader of such a bike forum sees exactly the same survivorship bias as the reader of this forum.

Well yes, they're trusting to luck. And anyone who flies out of KVLL is also trusting to luck, as engine failure on takeoff is highly likely to result in an accident causing at least severe injury, the Cherokee pilot who managed to put down in the Walmart parking lot a few years back notwithstanding. Anyone who flies in VT is trusting to luck for similar reasons, unless they only fly in the Champlain valley or never leave the pattern. I would argue that flying involves a certain amount of trusting to luck - how much trusting one is comfortable with, and under what circumstances, is entirely an individual thing.I would manage the risk by not flying beyond power off gliding distance of shore in a single. Those who do so without survival equipment aren't "managing risk", they're "trusting to luck". Even still, life rafts are cumbersome, might not make it out of the plane before it sinks and life vests are supposed to be inspected and certified and what might be suitable for a river or stream isn't good for off-shore use. Rental planes may not have them available due to lack of demand. It takes an effort to be equipped properly.

Yes, MTW --> LDM is the narrow point where it's possible for a NA single to eliminate the wet footprint. I've never been high enough to completely eliminate it, but at 10,500 it's down to about 10 minutes in a Cardinal RG, which I find acceptable as long as I don't do it too often.I've crossed Lake Michigan in my Comanche (MTW --> LDM) where I haven't had a wet footprint.

How would you calculate it? Wind increases with altitude, changes direction too. You'd have to have a pretty sophisticated algorithm to figure it out and where do you get the real-time data to make it reliable? Best you can do, IMO, is guess at the time you're at risk. If you become a glider, though, flipping a coin might be the only chance you have to head in the right direction.I haven't calculated exactly how high you would need to go, and of course it depends on the airplane (and the winds), but in a Cardinal it is probably around 9000 feet.

This reminds me of a guy I gave an intro flight to years ago. He went on to become a CFI and was taking a trip south over West Virginia in a student's plane. Lost the engine on takeoff, IIRC, and landed in a rocky stream rather than crash into the trees. Unfortunately, he drowned.And anyone who flies out of KVLL is also trusting to luck, as engine failure on takeoff is highly likely to result in an accident causing at least severe injury...

This reminds me of a guy I gave an intro flight to years ago. He went on to become a CFI and was taking a trip south over West Virginia in a student's plane. Lost the engine on takeoff, IIRC, and landed in a rocky stream rather than crash into the trees. Unfortunately, he drowned.

dtuuri

All such calculations either make assumptions about the wind, or neglect it completely. I disagree, though, that flipping a coin is as good as an educated guess when it comes to deciding which direction to try to make it to shore. Winds aloft forecasts aren't guaranteed, but they're certainly better than random chance, and many days they're accurate enough for that purpose.How would you calculate it? Wind increases with altitude, changes direction too. You'd have to have a pretty sophisticated algorithm to figure it out and where do you get the real-time data to make it reliable? Best you can do, IMO, is guess at the time you're at risk. If you become a glider, though, flipping a coin might be the only chance you have to head in the right direction.

Not sure if you're familiar with the area around VLL. It's suburban, with no open areas large enough to land safely in. Think residential neighborhoods, industrial strips, streets. Local lore says to land on the railroad tracks about a mile west of the field, but that only works from downwind on 9 (the runway would of course be a better choice) or if taking off on 27, and I wouldn't be at all confident of being able to walk away. In a fixed gear plane you would likely flip; in my RG if I decided that was my best option, I'd land gear up.This reminds me of a guy I gave an intro flight to years ago. He went on to become a CFI and was taking a trip south over West Virginia in a student's plane. Lost the engine on takeoff, IIRC, and landed in a rocky stream rather than crash into the trees. Unfortunately, he drowned.

Not sure if you're familiar with the area around VLL. It's suburban, with no open areas large enough to land safely in. Think residential neighborhoods, industrial strips, streets. Local lore says to land on the railroad tracks about a mile west of the field, but that only works from downwind on 9 (the runway would of course be a better choice) or if taking off on 27, and I wouldn't be at all confident of being able to walk away. In a fixed gear plane you would likely flip; in my RG if I decided that was my best option, I'd land gear up.

No, but if you can point me to a database where I can search for the accident by his name I'll post it.Got the NTSB link?

By its nature, flying is all about managing risk…because risk pervades the flying environment. Tolerance for risk varies considerably from person to person. If someone doesn’t feel comfortable taking certain risks then don’t take them…nothing wrong with that. When it comes to flying over cold water without the requisite safety equipment, the data clearly show that ditching in such conditions is a “low probability” ”high severity” risk. Many single engine airplanes do in fact fly over water, and ditching is statistically infrequent. So we each make our call on such matters. That’s what it means to be PIC!!

If the “high severity” aspect gives anyone pause, lest we forget that flying airplanes is inherently the same type of risk…i.e., “low probability” “high severity” risk of injury/death. While its perfectly normal to accept/reject different activities even though they are in a similar (objective) risk category, let’s not allow those personal choices to skew our understanding of the risk landscape.

I’m reading numerous examples of people engaging in risk subjectification, which is counterproductive. What do I mean? Let’s say that I determine I’m not going to participate in a certain activity because I perceive it to be “unwarranted” based on my personal risk/reward metrics. We all form a risk/reward scale that we base decisions on. The subjectification happens when I take the extra step (often subconsciously) from viewing the activity as too risky “for ME” to perceiving it as too risky for ANYONE. Once this leap has been made its very easy to perceive those that assume risk beyond what I’m comfortable taking as exercising bad judgment, or acting in an unsafe/foolish manner. Haven’t we all encountered this point of view in our journeys? Certain personality types (e.g., the Mother Hen syndrome) that seem particularly comfortable telling others the error of their ways? So when I read folks stating as fact that choosing to fly over cold water is not “managing risk” but rather “trusting to luck” I know the clucking has begun.

Every pilot has received the legally required education and testing with respect to the risks associated with flying in order to earn their license. Like it or not, THAT is the legal metric. Now we all know that just like every person that gets a driver’s license isn’t the wisest or most competent driver, so too is it with pilots. That’s life in the imperfect and risky world we live in. Personally, I won’t join the clucking in an attempt to cast a negative light on someone’s judgment because they choose to take risks that I won’t.

BTDT in a Citation II. Nice little airport. You could always land on a factory roof.Not sure if you're familiar with the area around VLL.

Uh-huh. In a helicopter, you mean.BTDT in a Citation II. Nice little airport. You could always land on a factory roof.

dtuuri

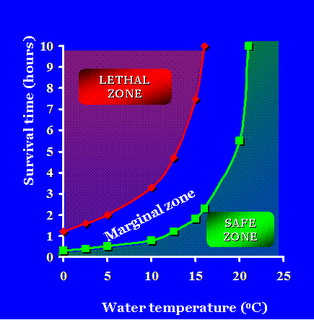

Everyone's risk management process is different. You could also argue that if we never fly GA aircraft our survivability for GA mishaps is nearly 100% (.. if one doesn't crash on our house)... I don't care what that chart says is "survivable", I demand a higher quality of survivability.

dtuuri

The airplane doesn't know it's over the water. Do the lakes to Osh all the time,also trips to the Bahamas.

Yes, i have ferried plenty of light planes fom florida to south africa via brazil. And no, i won't fly my family across lake michigan, we go around.

Once you learn to ignore "automatic rough" you are fine.