brcase

En-Route

Been my month for Carb Heat issues.

After previously having some issues with throttle cables I have developed the habit of checking the cable connections to the carburetor as best I can during the preflight. Earlier this month found a Cherokee where the Carb Heat cable that had become disconnected (probably would have found it on the run up also).

Then 2 hours into a 3 hour flight with a Cessna 140, had the carb heat cable fail and the carb heat defaulted into the On position, causing about a 500 RPM Drop after leaning a bit more and I assume melting a bit of ice it turned into a 150 RPM drop until I could land to get it fixed. It did take a surprising amount of time for the RPMs to come back.

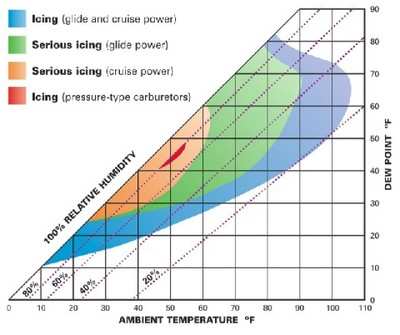

This morning I was flying a Cessna 150 35F and 93% Humidity. Runup was normal but perhaps a hint of ice during the carb heat check (250 rpm drop then came up to 150 drop). I took off with what seemed like normal TO power at about 400 feet RPM's started dropping, I pulled the carb heat and power dropped to about 2100 RPM which pretty much stopped my climb at about 500 feet. I started a close in turn back toward the runway but proceeded down wind keeping the runway withing gliding range, about midfield power started coming back up to normal. Probably took at least a full minute (seemed longer) to get back to full power.

Brian

After previously having some issues with throttle cables I have developed the habit of checking the cable connections to the carburetor as best I can during the preflight. Earlier this month found a Cherokee where the Carb Heat cable that had become disconnected (probably would have found it on the run up also).

Then 2 hours into a 3 hour flight with a Cessna 140, had the carb heat cable fail and the carb heat defaulted into the On position, causing about a 500 RPM Drop after leaning a bit more and I assume melting a bit of ice it turned into a 150 RPM drop until I could land to get it fixed. It did take a surprising amount of time for the RPMs to come back.

This morning I was flying a Cessna 150 35F and 93% Humidity. Runup was normal but perhaps a hint of ice during the carb heat check (250 rpm drop then came up to 150 drop). I took off with what seemed like normal TO power at about 400 feet RPM's started dropping, I pulled the carb heat and power dropped to about 2100 RPM which pretty much stopped my climb at about 500 feet. I started a close in turn back toward the runway but proceeded down wind keeping the runway withing gliding range, about midfield power started coming back up to normal. Probably took at least a full minute (seemed longer) to get back to full power.

Brian