Not a war story, but

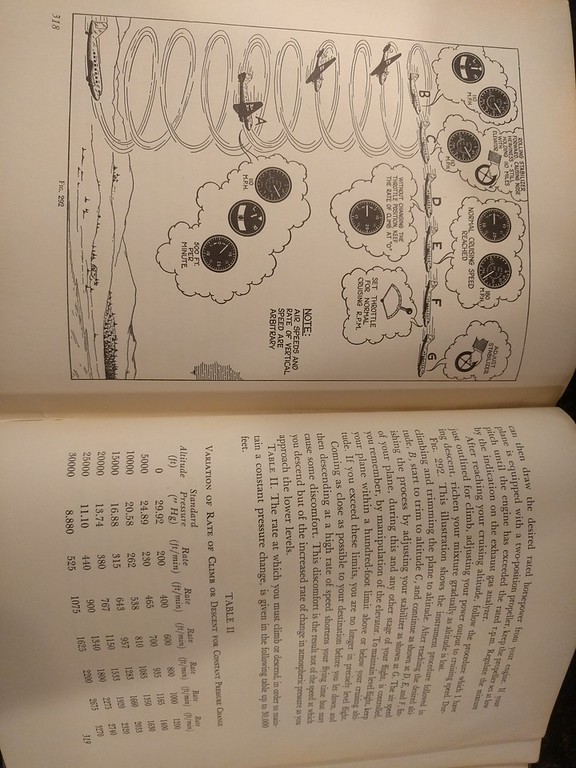

North Star over my Shoulder by Bob Buck is a great book that touches on a lot of the navigation techniques used in the early days. He talks about some pretty squeaky instrument approaches in airliners, mostly using the four-course radio range and occasionally a fan marker, as well as climbing up into the bubble with a sextant. It's interesting stuff for anyone asking the kinds of questions the OP asked.

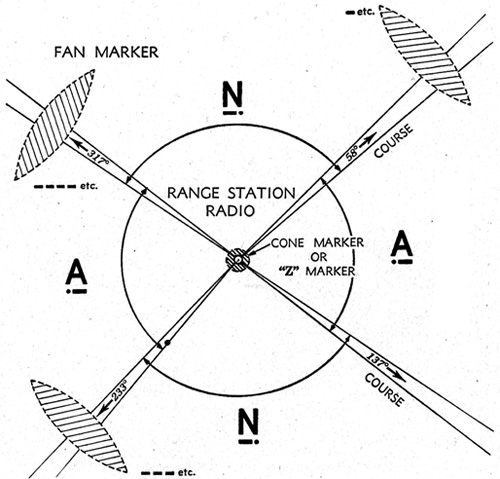

If you look into the history of ground-based aids to navigation, there were more or less 4 periods from what I can tell. The visual air mail route beacons, the four-course range, the VOR, and the GPS. The real transition to VOR seems to have been after WW2 although the technology was available during the war. And apparently the four-course range stations were often converted to NDBs along the way. The article about them on Wikipedia is instructive and includes both a chart excerpt and an approach plate that help get your head around how they were actually used.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Low-frequency_radio_range

My own thoughts about instrument flying during WW2, not confirmed by anything more authentic than daydreaming, is that there wasn't much IFR flying to be done. The fighters were either interceptors sent up to shoot down bombers or escorts sent to shoot down interceptors that are trying to shoot down bombers, and both of those missions are VFR in nature both because the bomber missions were VFR and because it's really hard to dogfight in a cloud.

The bombers were mostly VFR missions, at least when it came to dropping bombs on visually-identified targets (which could have been as small as a factory or as big as an entire city). The bomb runs were a matter of navigating to a visually identifiable initial point, then flying the final course to the target, and dropping your bombs on target. So you didn't need any kind of instrument navigation at the target, but you needed a good navigator who could use a compass, stopwatch, chart, and/or sextant to find the IP and to find your way home after the mission.

As far as instrument approaches, any kind of radio beacon on the ground would just lead the enemy to your base, and if you turned it on only when it was in use that would just make things worse by telling the enemy when it's a good time to bomb your base. So my suspicion is that the bombers and escorts only flew missions when it was VFR at their base as well as at the target, and interceptors only had to fly when it was VFR at their base, otherwise there wouldn't be bombers coming in for them to intercept.